One of the most consistent themes we hear from clients is that their greatest strategic challenge is retaining and attracting talent. We’ve all heard about “the Great Resignation,” “ghosting,” shifting worker preferences post-COVID-19, even the recent study that found that millennials would rather be unemployed than unhappy at work.

But the root cause of the staffing difficulties faced by credit unions – and all American businesses – is a matter of simple math. This article will present the numbers behind those challenges, a forecast of how long we might expect them to last, and some considerations that you might want to discuss to address the prolonged challenge.

Job Growth vs. Job Recovery

First, let’s differentiate between job growth and job recovery. Job growth occurs during a healthy economy when businesses and consumer activity are expanding. In a recession, jobs are lost. As the economy begins to recover from a recession, job growth resumes. However, until total employment returns to the pre-recession level, the resumed job growth isn’t really job growth, it’s job recovery. In other words, while economic activity is expanding, the jobs being added to non-farm payrolls (the measure of total employment) are replacing the jobs lost during the recession.

The 2020 recession was unique in that it was entirely manufactured. It did not occur due to variations in the business cycle, a geopolitical event beyond the control of policymakers, or some naturally occurring economic shock. It was created by policymakers in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: they intentionally shut down economies across the globe. In the process, more jobs were lost than in the eight previous recessions, from 1960 through 2009. And during the COVID-19 shutdown, the job losses occurred in just two months, whereas the cumulative job losses in those eight previous recessions were incurred over a total of more than 100 months.

Job Recovery Since the COVID-19 Shutdown

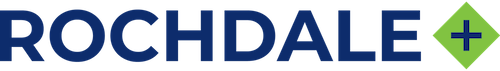

Much has been made of the jobs gained since the COVID-19 shutdown. In just six months after the economy re-opened in May 2020, non-farm payrolls increased by a record 11.8 million, an average of nearly two million per month. Since January 2021, payroll growth has exceeded 8.4 million, an average of 562,000 per month. This is well in excess of the “normal” job growth average of approximately 175,000 per month from 2017 through 2019, when the economy was in a normal growth phase.

However, as noted above, the jobs “gained” since the COVID-19 shutdown were not really jobs “gained,” but jobs “re-gained.” Figure 1 below illustrates that we still have not recovered all the jobs lost due to the COVID-19 shutdown. Prior to the shutdown, in February 2020, non-farm payrolls totaled 152.5 million. As of March 2022, the total was 150.9 million. Thus, the labor market remains nearly 1.6 million jobs short of full recovery.

Figure 1

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

But Wait, There’s More

At the current pace of job gains – 562,000 on average per month since the beginning of 2021 – we might assume that within about three months, that 1.6 million job deficit would be fully recovered, and we’d be back to where we were pre-pandemic. That’s a reasonable assumption. So let’s say that we fully recover to the pre-pandemic level of non-farm payrolls by June 2022.

And we might further surmise that once we reach that point, the labor market challenges we’ve been facing will begin to abate. However, that assumes that the economy is static. In other words, it ignores economic growth.

If the jobs added since the COVID-19 shutdown represent jobs re-gained, we have not added jobs to reflect economic growth. And the economy was indeed growing, organically, prior to the recession that was engineered as a response to the pandemic. Thus it’s safe to assume that, had policymakers not shut down the economy in response to the pandemic, the economy would have continued to grow apace.

Since job gains due to economic growth from 2017 through 2019 averaged about 175,000 per month – and there were no indicators on the horizon prior to the pandemic that suggested any disruption to the trend – we can assume that jobs may have continued to grow at that pace through the present. That would have added another 4.9 million jobs to non-farm payrolls from the initial shutdown in March 2020 through June 2022, our projected full recovery month.

In other words, even when we reach full recovery of the jobs lost due to the COVID-19 shutdown on a static basis, we may still be nearly 5 million jobs behind the normal growth trajectory on a dynamic basis. And economies are dynamic, not static.

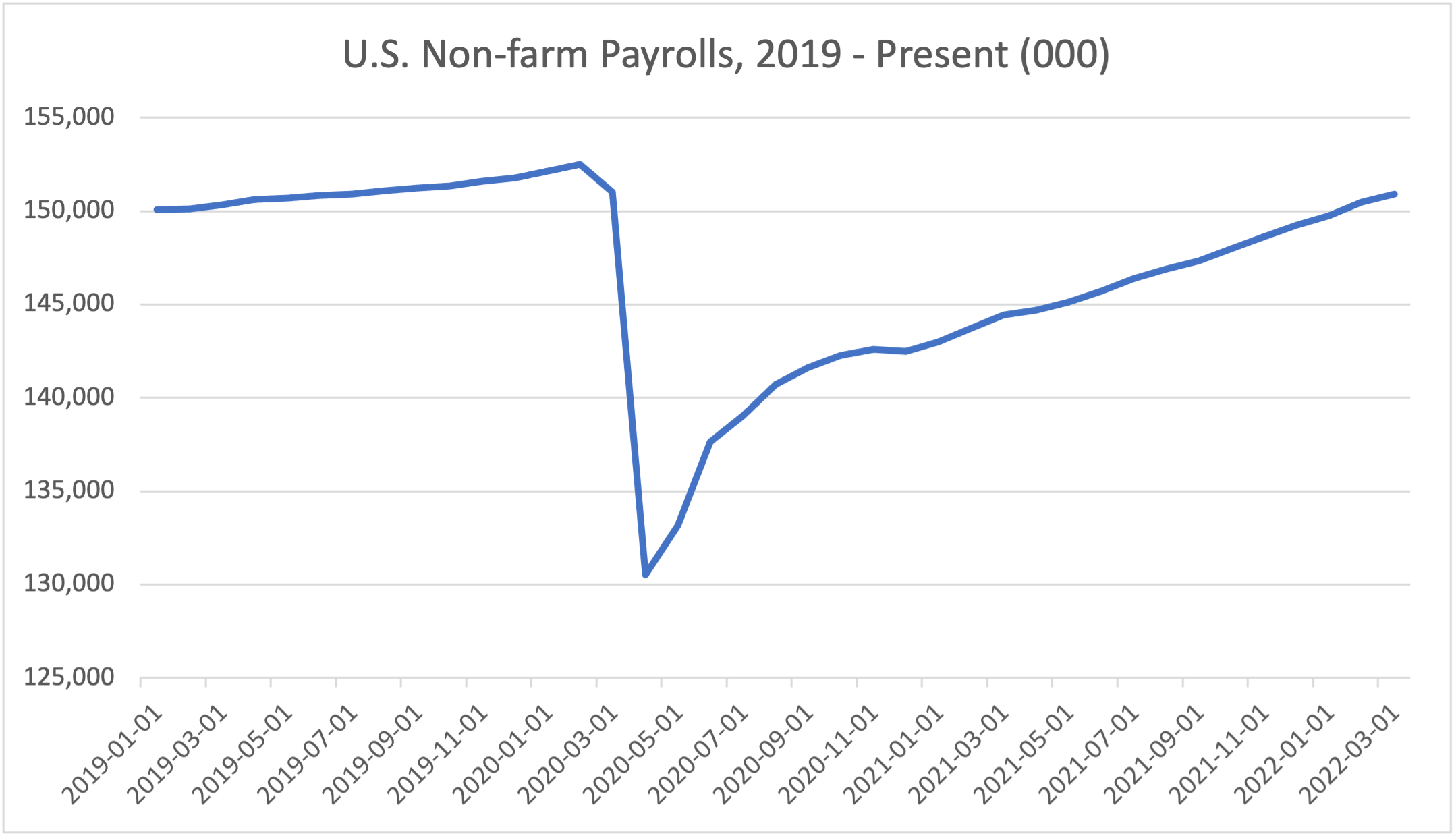

If we assume the economy had never shut down, and payrolls had continued to grow at 175,000 per month, total payrolls would have reached nearly 159.7 million by July 2023. With the shutdown, after recovering all jobs lost, the economy would have to continue to add 562,000 jobs per month – the average since the beginning of 2021 – to eclipse that total by then. This is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Obviously, if job growth slows from the January 2021 – March 2022 pace from now through July 2023, it will take longer to recover the sum of jobs lost due to the shutdown and jobs “behind” the growth trajectory.

One More Thing

But there’s one more consideration. We’re assuming, in this illustration, “normal” job growth of about 175,000 per month would have occurred had the economy not been shut down. However, massive amounts of fiscal and monetary stimulus have been infused into the economy, which have spurred economic activity that has fueled above-normal job growth. Thus, a portion of the jobs recovered have been stimulus-driven.

Another way to look at it is this: if that much stimulus had been applied to a normal economy, job growth would have been considerably more than 175,000 per month. Thus, the “break-even,” or “catch-up” point, is likely well beyond July 2023.

This explains why job openings have stubbornly averaged more than 11 million each month since July 2021, compared with the 2017-2019 average of less than 6.8 million: there is a huge surplus that is the result of a massive backlog. That backlog is a function of three things:

- We have not yet fully recovered all jobs lost due to the shutdown of the economy,

- We have not added jobs to account for economic growth since February 2020, and

- We have not added jobs to account for above-trend growth fueled by record economic stimulus.

Until this backlog is cleared, businesses will continue to face challenges in attracting and retaining talent. We can attribute it to changing workplace dynamics, catchphrases like “the Great Resignation,” or myriad other factors, and there would be some merit to those attributions.

But the overriding issue is one of supply and demand, and a matter of simple math. And it appears that it may be 18 months or so before the numbers reach equilibrium, and that issue is resolved.

So … What Do We Do About It?

To some degree, we just have to buckle down and live with it, because it isn’t going away anytime soon. However, there are some things that can be done to improve your competitive position as an employer that will aid in both retention and talent acquisition:

- Ensure that you offer competitive pay and benefits. Focus especially on benefits, as rising inflation and health care costs eat into Americans’ budgets.

- Strategically outsource, partner, and automate. Partnering with FinTechs can kill two birds with one stone by turning potential competitors into partners, while eliminating the need for internal staff resources.

- Eliminate unnecessary tasks. Businesses too often wait until an economic slowdown to “get lean,” but this is an excellent time to focus on efficiency. That will eliminate the need to make difficult decisions when the next downturn comes.

- Offer retention bonuses to slow retirements and other departures and offer “stay bonuses” to new hires who remain on the job for a reasonable period of time – say, six months. Many companies are doing the latter, and it’s a good way to combat the “ghosting” trend.

- Consider the intangibles. There’s an age-old debate about business attire. On the one hand, those who favor it argue that one needn’t dress like a slob to be comfortable. The counter-argument is, “My professionalism doesn’t hang in a closet.” Ask yourself whether non-member-facing personnel really need to wear a suit and tie, as most people would prefer not to. You may believe that your culture dictates it, but don’t let your culture get in the way of being competitive. Allowing casual attire is a free perk that doesn’t cost the enterprise anything – and it saves employees money in the form of dry cleaning costs.

- Another example of an intangible: my first action as a new CEO was to buy a movie theater popcorn machine for the break room. The cost was about $600. We had fresh popcorn on Fridays, on days we hit sales targets, to celebrate birthdays, and on other occasions. The staff loved it. I’ve since seen them in the branch lobbies of a couple of credit union clients, for both members and personnel.

- Be flexible! I can’t stress this enough. Where possible, offer flexible work schedules, remote work, job sharing, and other flexible work arrangements. Think outside the box. Remote work in particular can be instrumental in expanding your potential labor pool, and also retaining key talent that might leave due to relocation, of a spouse or for other reasons. Again, if you believe remote work doesn’t align with your culture, re-think whether you want to let rigid adherence to culture get in the way of being competitive.

As with all challenges, this too shall pass. We got through the housing crisis, we got through the pandemic, and we’ll get through this.