President Trump’s proposed policies – cutting taxes, imposing tariffs, streamlining government, and slashing regulations – are no different than his policies from his first term. So we can look at what he did then, and the results, as a gauge of what to expect from a second term. The key differences are the Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE, the fact that he appears to have more of a mandate now, and the fact that he has the experience of having been in Washington before, so should be able to navigate the political environment more effectively.

Before I go any further, a couple of caveats are in order. First, these prognostications are my own. They do not reflect any position taken by Rochdale. Second, I maintain political agnosticism in making my projections. I go where the data leads me, and don’t let political views bias my outlook.

With that out of the way, let’s look at the primary economic policy positions that were proposed during the campaign: tariffs, taxes, regulations, and government efficiency, and then we’ll touch on overall economic performance.

Tariffs

The opposition’s campaign talking point was that tariffs would cause a spike in inflation. This was an intentional strategy, since inflation was a pain that was currently being felt by all Americans, and the fear of even higher inflation would hopefully sway voters. But is it a legitimate argument – do tariffs cause inflation?

First, let’s define tariffs. A tariff is a tax imposed on the importer of foreign goods. The importer directly pays the tariff, then it’s up to the importer whether it wants to pass that cost along to consumers in the form of higher prices, which would indeed produce inflation. So, all else being equal, tariffs would result in increased inflation. However, economies are dynamic. All else is never equal. There are many moving parts behind inflation.

Whether tariffs will result in increased inflation depends on a number of factors: the propensity of the target country to absorb part or all of the cost of the tariffs; the propensity of the importer to absorb part or all of those costs; the availability of substitute goods, at both the intermediate and finished stages; and other factors that may offset higher prices resulting from tariffs, including subsidies for domestic producers, lower prices for unrelated products that are components of overall price indices, and Fed policy that may counter the effects of inflation. All of these factors may mitigate any inflationary impact that tariffs might have.

During Trump’s first term, his administration imposed a variety of tariffs on different countries. Beginning in January 2018, tariffs were imposed on solar panels and washing machines from China. In March through June, tariffs were imposed on steel and aluminum imported from all countries, and tariffs on China were expanded. Many of the tariffs were lifted by mid-2019, though some of the tariffs on China remained in place (and in fact were maintained under the Biden administration). What happened to inflation during this period?

Fig. 1

As Fig. 1 above illustrates, inflation, as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) year-over-year, was about 2.2% in January 2018, when the first tariffs were imposed under Trump’s first term. By mid-2019, when most of the tariffs had been lifted, CPI y/y was 1.7%, a half-point drop. Did tariffs cause inflation to decline? Of course not. But neither did tariffs cause an increase in inflation. Why not?

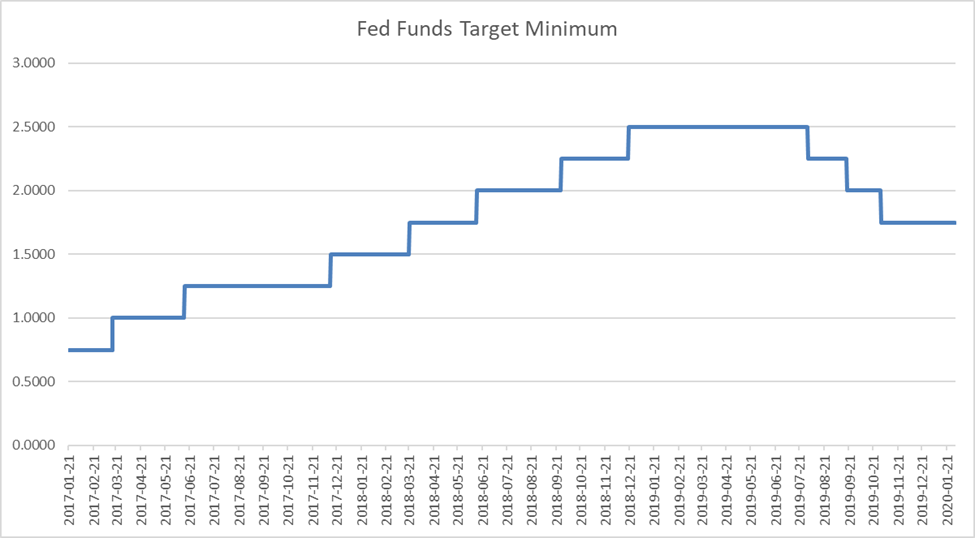

For one thing, the Fed was raising rates during that period, which is the monetary policy response to rising prices. Fig. 2 below shows the Fed funds target minimum during that same period. When the first tariffs were imposed, the funds target was 1.50%, and the Fed had already tightened by 100 basis points (bp). By the time the tariffs were lifted, the tightening cycle was completed, and the target rate was another 100bp higher than when the first tariffs were imposed.

Fig. 2

Other mitigating factors were also at play during Trump’s first term. One notable aspect of his use of tariffs is that it goes beyond the traditional reasons that countries impose tariffs, which are to support domestic trade and, to a lesser extent, to raise government revenue. Trump also uses tariffs as negotiating leverage to get what he wants, sometimes on policy fronts that have nothing to do with economics or trade. Often, the mere threat of tariffs brings trading partners to the table, Trump gets what he wants in terms of those other policy demands, and the threatened tariffs are never imposed.

In 2018, the tariffs imposed on China were not only in response to unfair trade practices, but also to theft of U.S. intellectual property. Chinese theft of U.S. IP continues today, to the tune of about $0.5T/year. China absorbed more than 75% of the 2018 tariffs, because it was in its economic interest to do so – the U.S. market was too important to Chinese commerce to risk losing it. It’s even more in China’s interest to absorb the bulk of tariffs now, as its economic standing is more fragile today than it was then.

Substitute goods also played a role during Trump’s first term. The U.S. sourced intermediate goods from Vietnam and other countries rather than turning to China, and thus was able to avoid higher prices. That further pressured China, which was one of Trump’s goals. He ultimately was able to reach a trade deal with China in early 2020, though China didn’t uphold its end of the deal once Trump left office, which is one reason he’s threatening even harsher tariffs on China in his second term.

Subsidies were also used during Trump’s first term. When Canada and China imposed retaliatory tariffs on U.S. agriculture exports in July 2018, the Trump administration revived the Depression-era Commodity Credit Corp. (CCC) to subsidize American farmers to offset the effects of those tariffs. And when India imposed retaliatory tariffs on U.S. ag exports in June 2019, the CCC subsidies were expanded.

Lower oil prices could also be an offset to any increase in the prices of imported goods in the overall inflation picture. Energy costs represent more than 9% of CPI, and economists are forecasting a 20% decline in oil prices under Trump’s proposed energy policies.

Finally, the threat of tariffs was used to bring about policy concessions during Trump’s first term. Besides the trade deal with China, Trump announced a series of escalating tariffs on Mexico in May 2019 unless that country delivered what Trump wanted in terms of border policy. The Mexican government immediately came to the negotiating table, and in June delivered what Trump wanted, and the tariffs were never imposed.

We’re beginning to see some of this now. As soon as Trump threatened tariffs on Canada and Mexico over border policy, the Mexican President called the President-elect to initiate discussions, and Canada’s Prime Minister flew to Mar-a-Lago to meet with Trump. If I were a betting man, I’d bet that Trump gets what he wants with respect to border policy from both countries, and that not a dime of tariffs is imposed on either nation.

Taxes

Every Presidential candidate makes promises regarding taxes, but they need Congress to act – the tax code can’t be changed by Executive Order. However, the likelihood that Trump will be able to achieve his agenda, at least through 2026, is increased by the fact that the Republicans control both houses of Congress. As regards tax policy, this may be offset somewhat by the stark reality of the nearly $2 trillion deficit, the very slim margin of control by the GOP in the House, and the history of dysfunction on the part of House Republicans.

Trump’s campaign proposals related to taxes were primarily as follows:

- No taxes on tips (which was copied by Vice President Harris)

- No taxes on overtime pay

- No taxes on Social Security income

- Consumer loan interest deductibility

- Making the 2017 Trump tax cuts (the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, or TCJA) permanent

- Many of the provisions of those tax cuts are scheduled to expire at the end of 2025

He also hinted at further reducing the corporate tax rate to 15% from 21%, the level that resulted from the TCJA.

Here’s my analysis of each of these proposals, as well as my best guess as to what to expect. Again, this is just my take.

No taxes on tips: There is some economic rationale behind this concept; tips are paid by you and me, using after-tax income, so there’s a double-taxation argument against taxing that income again. (Of course, there are other taxes that constitute double-taxation, and Congress is fine with that.)

No taxes on overtime pay: There is no economic rationale behind this idea. Companies pay regular wages as a pre-tax operating expense, and they also pay overtime as a pre-tax operating expense, so there’s no double-taxation argument. There’s just no rationale for this notion other than buying votes.

No taxes on Social Security (SS) income: There is some momentum behind this. Only nine states currently tax SS income at the state level, and three states eliminated state income tax on SS income within the last two years. However, the Social Security fund is projected to run out of money by 2035, so this proposal is unlikely to pass outside of a broader entitlement reform package (which is sorely needed).

Consumer loan interest deductibility: This would reverse the phasing out of the deductibility of consumer loan interest by the Tax Reform Act of 1986 under President Reagan. It’s intriguing, especially given the current high levels of credit card indebtedness and the cost of vehicles. Ultimately, it will come down to the cost of including this in a tax package.

Making the TCJA tax cuts permanent: This will be the administration and legislative priority. If they get nothing else done on taxes, they will target getting this done. Fig. 3 below shows the tax brackets under TCJA, and if TCJA is allowed to expire at the end of 2025 (income levels are not specified; they vary depending on filing status, and they change annually).

Fig. 3

In addition, if all the provisions of the TCJA were to expire, the standard deduction and Child Tax credit would fall by roughly half; the State and Local Tax (SALT) cap would expire (this would benefit taxpayers in high-tax locales like New York City, Hawaii, etc.); and the estate and gift tax exclusion would fall by half.

In summary, this is what I believe we can expect in a tax deal:

- The TCJA individual tax brackets will be made permanent (note that “permanent” only lasts until another administration/Congress changes those rates)

- The TCJA Child Tax Credit limit and estate and gift tax exclusions will be made permanent

- The standard deduction and SALT tax cap will be negotiated

- No tax on tips: a 50-50 chance, at best

- No tax on overtime: a casualty of negotiations

- No tax on SS income will be deferred as part of overall SS/Medicare reform

- No change in the corporate tax rate (at 21%, it’s already 5th-lowest among G20 nations)

- Timing: sometime in 2025, after the Cabinet appointees from Congress have been replaced, so probably summer or fall

Regulations

I won’t go into a great deal of depth here, other than to say that Trump has stated on numerous occasions his desire to slash regulations, and he attempted to do so during his first term. His chances of success are better in a second term, now that he understands how Washington works, and given the change agents he’s nominated to lead key agencies. Also, the DOGE is committed to that effort (more on the DOGE later). And Trump’s nominee for Treasury Secretary, Scott Bessent, is committed to slashing banking regulations.

Bessent is a proponent of what he calls the “3-3-3 Policy”:

- Cut the budget deficit to 3% of GDP by 2028

- Spur GDP growth to 3% through deregulation

- Produce an additional 3 million barrels of oil (or equivalent) per day

While that sounds like an aggressive agenda, it’s achievable. Looking at Bessent’s second priority, he proposes accomplishing this by slashing banking regulations and overhauling the Inflation Reduction Act. (Note that GDP growth averaged 4.7% during Trump’s first term prior to the Covid pandemic.) If GDP growth averages 3% through 2028, reducing the deficit from the current 6.3% of GDP to 3% of GDP would require cutting the deficit by $700 billion, which should also be achievable, even with the tax cuts being made permanent (note that both corporate and individual tax revenues increased through 2022 after the TCJA was enacted). And increasing oil production by 3 million barrels per day would be only about a 14% increase. Given the planned shift in energy policy, that likely wouldn’t be a problem.

The DOGE

The DOGE will not be an actual agency or part of the government, and thus will require Congressional action or Executive Order to enact any proposed spending cuts. However, we’ve already seen Elon Musk’s influence on Congressional spending during the recent negotiations over the House spending bill. Musk brings not only a brilliant mind, business acumen, and technology expertise, but also the power of a social media platform (X, formerly Twitter) that can mobilize hundreds of thousands of voters to bring pressure on members of Congress. His partner in DOGE, Vivek Ramaswamy, shares his intellect and business and technology experience.

Musk has claimed that the DOGE can cut $2 trillion from the federal budget. This is doubtful. The U.S. can be described as “an insurance company with an army, funded by debt.” The insurance company is represented by Social Security and health care, which represent 50% of the budget. The army is represented by defense, whose outlays account for another 13% of the budget. And the interest expense on the debt is currently 10% of the budget and rising. Cuts in these areas would be challenging.

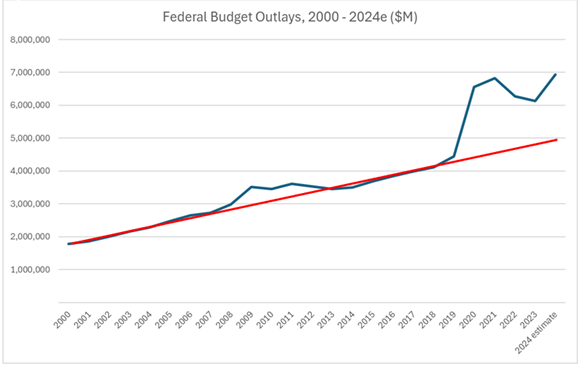

So that leaves just 27% of the budget that can realistically be cut. Total federal spending is around $7 trillion, so 27% of that is slightly less than $2 trillion. (Arguably, some defense spending can be cut, as there is undoubtedly waste there, but at the same time, President Trump wants to increase defense spending in some areas, such as building an “Iron Dome” defense system similar to Israel’s.) However, Fig. 4 below shows that there may be ample room to cut spending.

Fig. 4

Note that federal spending tracked along a steady trajectory from 2000 until the Great Recession. Then, stimulus payments and bailouts increased outlays through 2012, before spending got back on track through 2019. In 2020, massive ($3.4 trillion) spending on Covid – stimulus, PPP loans, vaccine development, etc. – ballooned spending, followed by another $1.9 trillion in January 2021 in the form of the American Rescue Plan. Spending declined in 2022 and 2023, but not by much. Then it increased again in 2024 due to payments to Ukraine, the effects of inflation, and increased interest on government debt. As a result, current spending exceeds what it would be had it returned to the trajectory that began in 2000 by … $2 trillion. Hmmm.

Musk and Ramaswamy have already used the power of X to solicit ideas for cutting spending, and they’ve already developed a DOGE website for the same purpose. Some examples of wasteful spending that have already been identified include:

- $1.5M to study the mating call of country frogs to see if it’s different from that of city frogs

- $1M to study whether selfies make one happy

- $100,000 to see whether sunfish are more aggressive when given gin or tequila

- $1.3B was paid from IRS, Medicare, and the VA to beneficiaries who were deceased

- $171M in unemployment and SS benefits were mistakenly paid to prisoners because they were counted as free, out of work citizens

- The Pentagon has failed its annual audit for a seventh consecutive year, unable to full account for its $824B budget

- The Government Accounting Office estimates annual government fraud losses of $233B-$521B

Clearly, there are opportunities to save money, and even some notable Democrats in Congress, such as Bernie Sanders and John Fetterman, have jumped on the DOGE bandwagon. While Musk and Ramaswamy may not be able to save taxpayers $2 trillion, if they can just save $700 billion over four years, they’ll have achieved Treasury Secretary-elect Bessent’s policy objective.

Overall Economic Performance Under Trump 1.0

Finally, let’s look at how the economy fared during Trump’s first term. We’ll examine that performance pre- and post-Covid.

The U.S. unemployment rate fell from 4.7% when Trump took office to 3.5% in February 2020, the lowest since 1969. As previously noted, GDP grew by an average of 4.7% during his first term up until the pandemic hit, which was nearly a point higher than during his predecessor’s two terms (removing the first few quarters of President Obama’s presidency, during which growth was anemic as the economy was coming out of the Great Recession). And from the time he was elected until just before the pandemic shutdown, the average annual return on the S&P 500 was 19%.

The effect of the Covid shutdown on the global economy was extraordinary. In just two months, March and April 2020, 22 million jobs were eliminated in the U.S. alone. In other words, the shutdown wiped out all the jobs added from the end of the Great Recession through February of 2020, a period of nearly 10 years. The unemployment rate jumped to 14.8% in April, the highest since the Great Depression. Nominal GDP was -6.8% year-over-year in 2020 Q2. And the S&P 500 fell 34% from February 19 to March 23. For reference, the index fell 51% during the Great Recession – over a 17-month period.

How did the economy fare from the time it re-opened (in some states) in May 2020 until Trump left office in January 2021?

- 57% of the jobs eliminated in March and April had been recovered, and that included more than 240,000 additional jobs lost in December 2020 due to resumed shutdowns in New York and California. It would take another 17 months – nearly twice as long – to recover the remaining 43% of jobs eliminated.

- The unemployment rate recovered 73% of the increased from the pre-Covid low. It would take another 20 months – more than twice as long – to recover the remaining 27% of the way to return to the pre-Covid low.

- Nominal GDP recovered to more than 100% of the pre-Covid level by year-end 2020.

- The S&P 500 recovered to more than 100% of the pre-Covid level by mid-August 2020, and was up nearly 11% from the pre-Covid high by year-end.

And, of course, the Covid vaccine had been fast-tracked through the otherwise bureaucratic FDA approval process, was in production, and was ready for distribution with a distribution plan in place by the end of Trump’s first term, paving the way for even broader re-opening of certain sectors of the economy. It’s also worth noting that household wealth increased by more than 35% on a nominal basis, and nearly 28% on an inflation-adjusted basis, during Trump’s first term.

Conclusion

It’s unlikely that we’ll see another Covid pandemic during Trump’s second term, and if we do, hopefully the policy response will be more measured and have less disastrous economic consequences. Based on a review of the data from Trump’s first term and an analysis of the situation leading into his second term, the economic outlook is positive, at least through the 2026 mid-terms. Barring excessive in-fighting among House Republicans, most of his agenda should move through Congress more quickly than during his first term, given the strength of his election victory and his greater experience in the ways of Washington. Fed policy also appears poised to flex toward his policy priorities.